Man & Nature

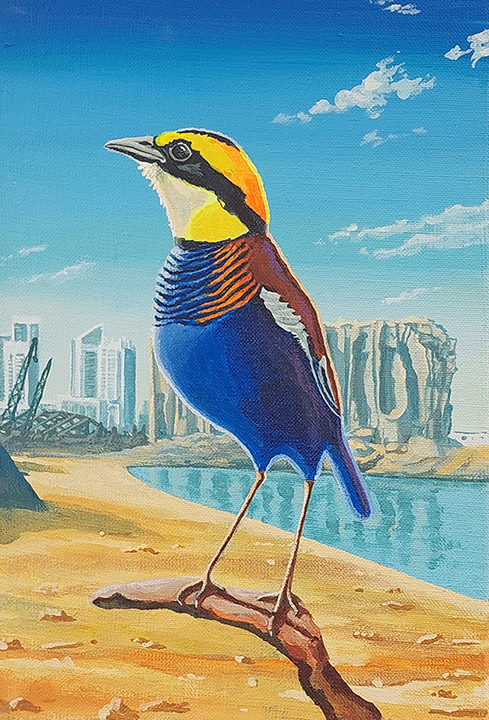

While Nature watched through the window, participants gathered at The Hague Peace Projects to facilitate her long overdue therapy session with Man. The evening welcomed a discussion about the environment with our three guest speakers and an art exhibition featuring the work of Jakob de Jonge and Steen Bentall.

Little did we realise that this would be one of the most meaningful and necessary discussions we should all have.

Man and Nature: two categories framed in opposition to one another. Though this may feel quite normal, it is a false dichotomy. With the gap between these two constructs deeply embedded in our culture and vocabulary, you would be forgiven for not giving it a second thought. Today was all about that second thought… and the thoughts that followed.

The event was moderated by Benjamin den Butter, a lawyer, elected member of the water authorities for Delftland, and member of the Partij vd Dieren (Animal party). Benjamin introduced the proceedings with a question posed by his daughter prior to the event. “Why is it Man and Nature, and not Humans and Nature instead?” she had asked. “I’m not sure I feel addressed here as I am not a man”.

A fair point, but in this case the use of the word Man was quite deliberate.

SDB

Excuse me, I have a question

Mainstream attempts to achieve environmental sustainability have been classified into three main approaches. Known as the technological, cognitive, and behaviourist approach, each has proven to be acutely unsuccessful. “While each of these groups contain variations, each is rooted in a particular way of viewing the relationship between humans (“Modern Man”) and nature” (1).

These approaches all function to reproduce modern mainstream culture. An alternative is the ‘cultural approach’ which recognizes a diversity of cultures and assumes modern capitalist culture as the root cause of environmental unsustainability.

“The cultural approach argues that although human behaviour can be rooted in human tendency for self-preservation, culture mediates these two … The cultural approach then asserts that modern mainstream culture is one major obstacle to achieving sustainability and therefore shifting the culture is essential to changing behaviour among the public for greater sustainability” (1).

As our guest speakers would establish throughout the evening, many cultures that have graced our history have built sustainable relationships with their environment. Unfortunately, societies that once hinged on sustainable reciprocity have now nearly all been conquered, lost to the realm of fading memories and forgotten stories. They live on in people blocking the highways, in the rebellious spirit of the young, in the exhausted environmental scientist who just can’t seem to get anyone to listen.

Those sustainable practices that do remain are embedded in a plethora of indigenous cultures that struggle to survive, their philosophies categorised as unprofitable in an economy that attributes no added value to Nature other than its exploitation.

JdJ

Our first speaker was Chihiro Geuzebroek, a multidisciplinary artist, writer, organizer, and trainer in decolonial climate justice perspectives and practices. Half Bolivian and half Dutch, Chihiro joined us live from Bolivia where she fights to protect local cultures and their habitat. As a Quechua grandchild born and raised in Amsterdam, she strives to preserve and learn from the invaluable indigenous knowledge that has accumulated over the past millennia, and thus help nourish a learning journey towards a sustainable culture shift.

A wealth of information has been passed down from generation to generation. Information containing everything we need to know about living off and with the local surroundings. And more importantly, how to do this sustainably by respecting the environment and maintaining it for the next generation.

Our knowledge and recognition of cultures such as the Quechua indigenous peoples of Bolivia remain severely lacking. With as many as 5000 surviving indigenous cultures in the world today, you would probably be hard-pushed to name just a handful. And while they account for 6% of the world population, they protect 80% of our remaining bio-diversity and enjoy no sovereignty whatsoever.

SDB

More relevant to true sustainabilty than the exploitative effects of new scientific knowledge are the native cultural attitudes that challenge our own Western laws and practices. Representing a complete paradigm shift in our interpretation of ‘Man and Nature’, they can be hard to imagine.

With no specific word for ‘nature’, these indigenous cultures are built on an appreciation of the symbiotic relationship between humans and their environment, each containing their own laws and practices of respect and reciprocity. From this perspective, there is no need for a word for ‘nature’; not only do the indigenous peoples of Bolivia feel no need to juxtapose this supposed ‘nature’ with themselves as ‘man’, they also understand one very simple, yet very important thing: we are a part of nature, not apart from it.

Without knowledge of these cultures, you may be inclined to think that a healthy symbiosis is not possible, or even unnatural, going by the laws of economics that govern our behaviour today. What we legally term as trade, profit, or development, is short-sighted crazy behaviour from a standpoint of respect for the intricate relationships between all things and the reciprocity between them.

With an arsenal of examples, Chihiro impressed upon us the importance of humankind’s cultural heritage and the fact that we cannot afford to forget it. Time is running out for our ecosystems and indigenous cultures as the global repercussions of our entitlement and economic servitude come to light.

That it takes the realisation of global implications to appeal to the importance of human and environmental rights is clearly disconcerting. And while we slow-motion realise that time is running out for all players in the game, it is precisely the indigenous communities, the poor, the Global South, that are suffering.

Mainstream attitudes towards entitlement, hierarchy, and growth are stubborn. They conform with capitalism’s systemic obsession with the ‘spoils of Man’ (aka ‘progress’) which manifests itself in an ever-expanding production (exploitation) for consumerism and the corporatisation of global resources, including citizens.

Chihiro’s battle deserves great admiration and the full support of us all. It will require a mammoth collective effort to convince a long history of class war and conquest to stop and think, but we have to try.

SDB

This interpretation of ‘Man and Nature’ received a legal perspective from our second speaker of the evening: Jan van de Venis – lawyer and founder of JustLaw, ombudsperson for Future Generations, and a rights of nature expert. Jan believes that mankind cannot own Nature, and that Nature in fact owns itself.

In severing the relationship between Man and Nature, the implications of nature’s exploitation have become structurally underrepresented in modern ‘Man-made’ society. As such, Jan claims it stands to reason that entities such as trees and rivers that make up ecosystems, receive some (legal) representation in decisions about their future – and thus the future of everything and everyone intrinsically linked to them.

Jan elaborated with an example of a vibrant ecosystem that has recently acquired the right to represent itself. The Wadden Sea in The Netherlands is a UNESCO World Heritage site and a dynamic ecosystem that is under threat due to pollution and gas extraction. By making the Wadden Sea its own legal entity, Dutch law has enabled it to own itself. As a result, the Wadden Sea officially enjoys legal representation and the governance to protect itself.

Thanks to lawyers like Jan, we are starting to challenge the traditional representation of parties in legal disputes about Nature. This allows for consideration of the consequences of exploitation and is a hopeful a step towards bridging the artificial divide between the cultural constructs of Man and Nature.

SDB

It may require a mental jump to consider giving rights to Nature. Yet, the more you understand the perspectives of different cultures, the more likely you are to appreciate our critical connection and interdependence with the world around us, and challenge the dichotomy of life and nature being seperate things.

There is a clear and immediate need to cherish and learn from the rich diversity of human cultures that have evolved to build sustainable relationships with their surroundings. We have a richness of stories, answers, and philosophies that provide real solutions to live off and maintain countless ecosystems. In essence, indigenous cultures are a human treasure trove of our hardest earned knowledge: intelligence on how to achieve a healthy planet for present and future generations of all life.

By now it had been well-established that indigenous peoples form a vital source of inspiration for developing a sustainable culture. Our third speaker Sophie Kwizera explained the consequences of unsustainable exploitation and the entrenched systems and attitudes of Man and Nature. Specialising in human rights, nature, and feminism, Sophie works for ActionAid and is responsible for investigating the real-life impacts of mineral supply chains. She laid out the devastating impacts of mining, which among other things can include water acidification, soil erosion, and the degradation of local ecosystems and communities.

Her report was as expected. With an entitlement that goes without saying, it is business as usual as companies continue to gouge out ecosystems, but this time in the name of windmills and solar panels, and the destructive mining that these ‘green solutions’ demand. And while the alarming consequences of this hunt for metals and minerals remain comfortably distant for many, the effects are already catastrophic for not-in-my-backyard-millions and encroach on us all in a pending global climate disaster for our children.

SDB

At this stage, we were trying to digest the big picture painted by our three speakers. It was a picture of a dominant, Western capitalist culture and its systems that excel in exploitation and unsustainability by design. We felt enlightened but chilled by this informed glimpse at the unfinished artwork of capitalism that aspires to destroy much of life’s diversity upon its completion.

The thoughts that followed were many. How to stay within the realm of what is both achievable and desirable, and how to discern real solutions from band-aid politics that just pass the problem on to future-us? Unfortunately, the search for solutions to the energy crisis are still guided by underlying colonial strategies of exploitation and profit-fetishisation. As it stands, the global economic system continues to demand increasingly higher energy requirements to satisfy its insatiable need for growth.

Those who believe that striving to meet an ever-increasing energy order with ‘green’ alternatives will lead to a sustainable relationship between planet and humans are sorely mistaken. The systemic insistence on growth and the accompanying entitled attitudes of exploitation are simply unsustainable, with respect to ecosystems as well as people themselves.

It is time to address the laws and practices that provide little resistance to the exploitation drive of the free market economy. It is time to reflect on our attitudes and systems, and to stop buying into the justifications of a wealthy entitled patriarchal class.

As Meireis and Rippl say in their book ‘Cultural Sustainability’: “If the political and social benchmarks of sustainability and sustainable development are to be met, ignoring the role of the humanities and social, cultural and ethical values is highly problematic. People’s worldviews, beliefs and principles have an immediate impact on how they act and should be studied as cultural dimensions of sustainability” (2).

SDB

What are you doing here?

So now what?

Creating attitude and system change is no small task, but there is every reason to do so. Present and future generations deserve an honest look at their inherited societal and systemic constructs. At what they mean, how they derived their meaning, and where they should take us.

It is not easy to unravel the systems that dictate our behaviour, to acknowledge the cultural traits that perpetuate entitlement and challenge colonial capitalism as the inevitable successor to everything. But it is in the arena of cultural reflection where each new generation fights for juster worldviews upon which our future hinges more heavily each time.

According to a recent survey, 90% of the Dutch population believe that humans are responsible for climate change, and 72% believe that humanity must take action to address it. It has become a question of empowering the agency of a civil society which is demanding change.

Given such figures, you would expect a democracy to be able to facilitate this process of change. Instead, it remains trapped in self-serving corporate and political media narratives and is still far from the empowering direct democracy that is needed.

And so it is possible, that at a time when there can be no doubt as to the severity of the climate challenge ahead of us, the Dutch government continues to subsidise the fossil fuel industry to the tune of more than 48 million euros every day. And that’s not even mentioning the army. Business is business says capitalism.

Looking ahead

The test ahead is to challenge the entitlement and hierarchy rooted in our way of thinking and doing. Most importantly, we must challenge capitalism and its systems that command our lives.

If we are to achieve a sustainable future of any kind, a durable culture shift must arise from an informed civil society that seeks to democratically decide its own future. The first step in this is to, at least, address the mainstream information diet of economic, political, and cultural framing and bias that keeps privilege out of reach of the democracies it holds to ransom.

SDB

Go another way

Our hope lies in the humanity of civil society and the ideals of direct democracy, best served with all the knowledge and facts we have. With over 5000 indigenous stories out there waiting to be heard, you might consider starting by sharing this one.

Without a significant culture shift from entitlement to respectful reciprocity, we will –among many other undesirable things– continue to rush headfirst into the next climate and humanitarian crisis.

Entitlement, alas, is headstrong by nature and requires a form of cognitive rebellion to escape its entrenched resistance to change. The quality of our solutions will depend on how well we are able to talk about this together. On how well we can hear different perspectives, grounded in knowledge and respect, to better understand our motivations, our doctrines, and the stories behind our assertions.

Little did we realise that this would be one of the most meaningful and necessary discussions everyone should be having.

The time for change is now. Don’t wait.

By Steen Bentall

References

1.

Komatsu, H., Silova, I. and Rappleye, J. (2023), “Education and environmental sustainability: culture matters”, Journal of International Cooperation in Education, Vol. 25 No. 1, pp. 108-123. https://doi.org/10.1108/JICE-04-2022-0006

2.

Meireis, T., & Rippl, G. (Eds.). (2019). Cultural Sustainability: Perspectives from the Humanities and Social Sciences (1st ed.). Routledge. https:/doi.org/10.4324/9781351124300

Recommendations

PODCASTS:

Chihiro Geuzebroek over klimaatrechtvaardigheid en kunst

Darko Lagunas: Is “duurzaamheid” wel de oplossing voor de klimaatcrisis?

Chihiro’s recommendations:

Playlist of climate reparations

Decolonial climate justice playlist

BOOKS:

Winona Laduke – ALL OUR RELATIONS

Nick Estes – OUR HISTORY IS OUT FUTURE

And not Indigenous but very essential decolonial – INFLAMED by Raj Patel and Rupa Marya

ARTICLE:

Living in Harmony with Nature? A Critical Appraisal of the Rights of Mother Earth in Bolivia

by Paola Villavicencio Calzadilla and Louis J. Kotzé

Share this page

Together we can Make Change!

Donate Now

Your one-off or monthly donation makes a big difference!

Follow us

Follow us on YouTube, Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook

Collaborate

Interested in collaborating or volunteering?