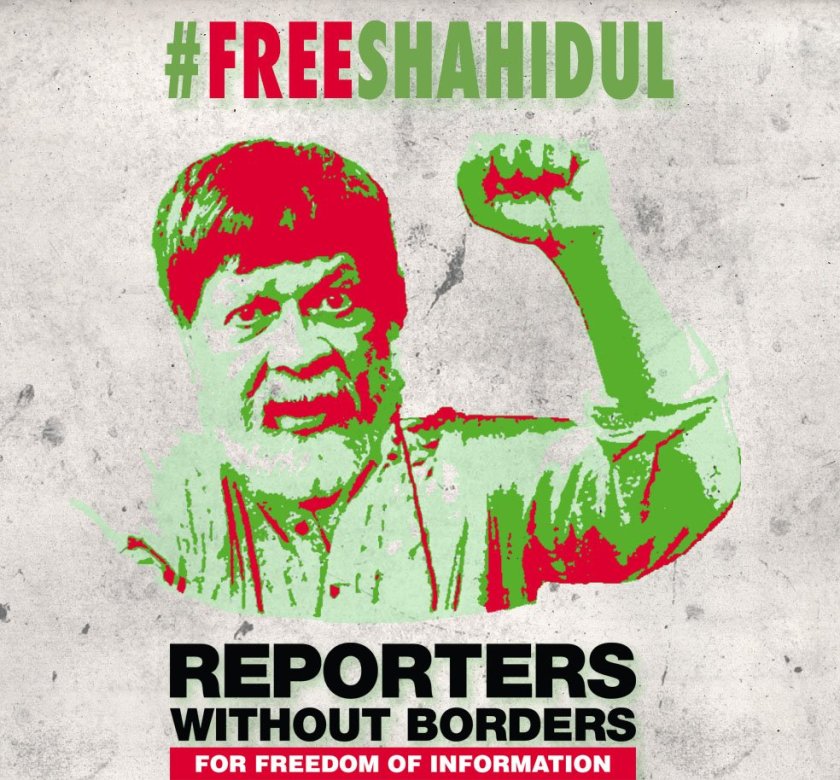

The power politics of law enforcement: Arrest of prominent photographer Shahidul under the unlawful ICT Act

Bangladesh 2019

After the death of two students in a road accident in late July 2018, protests sparked in Bangladesh’s capital Dhaka, with tens out thousands of students not only protesting the lack of government effort to prevent thousands of road deaths a year (1), but for the government to take responsibility for more burning issues (1). The peaceful protesters, however, were met with violence – police fired tear gas at students, pro-government students launched counter-attacks, and anyone documenting the incidents was stopped by extra constitutional means (1). A sentiment is spreading among the urban population: The time has come for the Government to restore the rule of law that the Bangladeshi Constitution guarantees (2).

The forced dissolution of the protests did not serve the purpose of securing public safety. Instead, it was a manifestation of efforts to silence those who publish evidence of any kind of violence. Human rights activist Sultana Kamal assessed that the “state automatically assumes [people speaking up about human rights] are talking against the state” (3). This assumption becomes clear in the story of Shahidul Alam. Shahidul, himself a photographer, documented the protests in early August, and later in a Skype interview with Al-Jazeera commented on the excessive use of force by the police and that he had observed (4). On August 5 2018, Shahidul was surprised by thirty to thirty-five officers from the Detective Branch; as CCTV had been taped up and footage was later confiscated, the sole account of the incident originates from the security guards of the premise, who had been tied and locked up by law enforcement (5).

Shahidul was apprehended on the basis of charges under the ICT Act. The Act was passed meaning to facilitate access to credible information and to close the “digital divide” within Bangladesh, but researchers have observed a “disconnect between the government’s Digital Bangladesh policy direction and the draconian features of the ICT Act” (6). Enacted in 2006 when the judiciary in Bangladesh had not yet fully become independent from the executive (8), the Act was amended on 6 October 2013 to include stricter provisions – for instance, offences under the Act are now non-bailable, and arrests can be conducted without warrants, as was the case with Shahidul’s arrest (6). Through the 2013 revision, the minimum sentence for the defined acts is now 7 years, and can extend up to 14. Its Section 57(1) reads:

If any person deliberately […] causes to be published […] in electronic form any material which is fake and obscene or its effect is such as to tend to deprave and corrupt persons who are likely, having regard to all relevant circumstances, to read, see or hear the matter contained or embodied in it, or causes to […] prejudice the image of the State or person or causes to hurt or may hurt religious belief or instigate against any person or organization, then this activity of his will be regarded as an offence.

The following commentary accurately sums up what Section 57 means for the freedom of speech in Bangladesh:

From the text of the Act it appears that even any innocent online posting can become a cyber crime […]. [The] crime doesn’t depend on the offensive or illicit nature of the posted material. It depends on the readers’ or viewers’ personality and attitude (8).

Freedom of Speech is guaranteed by Article 39 of the Bangladeshi Constitution; the right can only be restricted under clearly defined criteria which the purpose of the ICT Act does not meet (8). Freedom of Speech is also subject to Article 18 and Article 19(3) the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), ratified by Bangladesh in 2000 (9). The ICT Act is thus not only unconstitutional, but unlawful even beyond.

Detained on the basis of the unlawful ICT Act, Shahidul’s treatment equally violates his fundamental human rights. During his imprisonment, he has been tortured (UN Convention Against Torture), denied contact to his lawyer (Article 13(b) on the Right to a Fair Trial of the ICCPR) (10), and denied bail twice by a non-independent judiciary a violation of Article 14 of the ICCPR) (7).

It is a general principle of international law that states hold responsibility for their wrongdoings, and customary international law applies to Bangladesh as to that it may not invoke its internal law for treaty breaches. While the term “treaty breach” may seem quite technical, in this case it refers to serious violations of human rights. Shahidul is only one of many journalists, editors, professors and bloggers arrested on basis of the ICT Act, and the silencing of those who speak out against intolerable police brutality cannot be excused. Journalists and students are standing up for their right to be heard, and the violent suppression of both only indicates that Bangladesh’s rule of law is further deteriorating.

We at the Hague Peace Projects stand in solidarity with Shahidul. He, as many others, does not in any way deserve the prison term of seven years he will most likely be sentenced to, under an Act that was made by politics, not the law.

References:

- “Bangladesh: Mass Student Protests after Deadly Road Accident.” Al-Jazeera, August 02, 2018.

- “New Transport Law to Be Placed in House Sunday.” The Daily Star, September 12, 2018.

- “‘Rights Defenders Are Now under Threat’.” The Daily Star, September 13, 2018.

- “Bangladesh: Photographer Shahidul Alam Denied Bail in ‘cruel Affront to Justice’.” Amnesty International UK. September 11, 2018.

- Rahman Rabbi, Arifur. “Photographer Shahidul Alam Picked up from His Home.” Dhaka Tribune, August 5, 2018.

- Hussain, Faheem, and Mashiat Mostafa. “Digital Contradictions in Bangladesh: Encouragement and Deterrence of Citizen Engagement via ICTs.” Information Technologies & International Development 12, no. 2, 48-49.

- Hossain Mollah, Awal. “Independence of Judiciary in Bangladesh: An Overview.” International Journal of Law and Management 54, no. 1, 65 .

- Badruzzaman, Mohammad. “Controversial Issues of Section-57 of the ICT Act, 2006: A Critical Analysis and Evaluation.” IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science, II, 21, no. 1, 68.

- “Reporting Status for Bangladesh.” United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner.

- “Shahidul Alam Falsely Charged and Tortured.” Front Line Defenders.