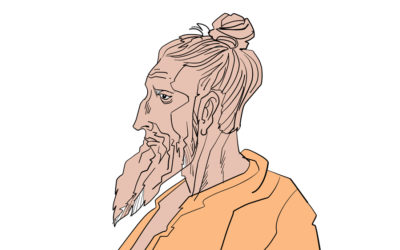

A Poet of Bangladesh’s Past and Present – a Tribute to Kazi Nazrul Islam on his 120th Birthday

Bangladesh 2019

“Of equality I sing: where all barriers and differences between man and man have vanished, where Hindus, Muslims, Buddhists, and Christians have mingled together.” [i]Bangladesh’s national poet, Kazi Nazrul Islam (*1899, †1976), sings of equality. He sings of peace. He sings, humbly, of respect and love for humanity, and for his homeland. He sings, hurt, of the divisions he has experienced, the hatred that pervades society. “I have turned mad having seen what I have seen, having heard what I have heard.” [ii] He sings, feisty, of revolt against oppression, and of rebellion against chains of ignorance. Of course, among his four thousand works, not all call out for a common humanity, but it is because of his strife for change that Kazi Nazrul Islam came to be known as the “Rebel Poet”.

His poetry is beautiful even when translated. As a non-Bengali native, it is impossible for me to know how unconceivably beautiful his language must be in his own tongue. His writings are flawless; even his earliest prose is so perfect that no effort could have improved it any further. It flows, so I was told, like a fountain, with a rhythm that wraps around the audience like a warm coat, and at the same time rallies every being to stand up for their rights, fuelling their drive to break out of the familiarity of oppression and ignorance. It is said that his language burns with a flame that is unprecedented in Bengali literature. Nazrul became Bangladesh’s national poet because of how uniquely it lets Bangladesh come to life – its nature, its objects, its symbols (both Hindu and Muslim!), its historical heroes (again, both Hindu and Muslim!), its contemporary hurt. Through his influence on new generations of poets, Bengali poetry as an art came closer to life.

Kazi Nazrul Islam was known as the “Rebel Poet” not merely because of his fiery language, or because of his desire to liberate Bengal from the British. Nazrul was a rebel because he refused to bow to anyone. [iii] It is true that he was a devout Muslim, and a proud Bengali – what he refused, however, was to be shoved into a categorization that he would have to be loyal to as an end in itself. In a speech delivered in Kolkata’s Albert Hall on December 15, 1929, he said:

“Just because I was born in this country and society, I do not consider myself to be solely a subject of this nation and my community. I belong to every country and everyone. The caste, society, country or religion within which I was born was determined by blind luck. It’s only because I managed to rise above these trappings that I could become a poet.” [iv]

Though Nazrul was not uncriticized or unopposed in his time, he gave people little reason to hate him. A devout preacher of religious symbols, he applauded religion if used as a language of love, and praised practices of various religions. Instead, it was fanaticism, superstition and ritualistic behaviour he spoke out against:

“Do consider the honour of martyrdom

more glorious than slavery,

Consider the sword to be nobler than

the belt of the peon,

Do not pray to God for anything petty;

Bow not your head to anyone except God.” [v]

“I am a poet of the present, and not a prophet of the future.” [vi] Nazrul may have claimed that his time may pass, that his writings would become outdated and inapplicable. Considering contemporary incidences of hatred in Bangladesh – riots, violent protests and extra-judicial killings – it is clear Nazrul’s dream has yet to be realized. As the national poet of Bangladesh, his poetry is taught in educational curricula, the national anthem of Bangladesh is a Nazrul song, and his person is celebrated on its own national holiday (today). Why his message has not pervaded society remains a mystery. After all, while Nazrul’s language may be magical and enchanting, his messages are never hidden. The audience need never engage long with his material. Instead, his poetry has been said to “communicate even before [it] is understood.” [vii]

It is true that his memory and dreams carry on in contemporary Bangladesh. In 2012, Bangladesh’s Prime Minister prominently declared:

“We want to build a Bangladesh as dreamt by national poet Kazi Nazrul Islam […] breaking the vicious cycle of poverty. We want to build a Bangladesh where every citizen will enjoy equal and basic rights. There will be no difference between the citizens. Women would enjoy their just rights. I urge all to work towards building such a Bangladesh. May Bangladesh Live Forever.” [viii]

On this day, his 120th birthday, we celebrate his legacy. Yet merely praising him with words is not enough, instead, our love for Nazrul should extend beyond a dull admiration, and encompass the spirit of rebellion that is so famously attributed to him. Our compassion should rise above the boundaries created by religion, caste, and social status, and should extend to joint humanness. Today, the rebel poet still has a cause to rebel for.

[i] Islam, Kazi Nazrul. Rebel and Other Poems. Sahitya Akademi, 2000, page 37

[ii] Choudhury, Serajul Islam. “The Blazing Comet.” New Age Xtra. June 1, 2006. Accessed May 16, 2019.

[iii] Choudhury, Serajul Islam. “The Blazing Comet.” New Age Xtra. June 1, 2006. Accessed May 16, 2019.

[iv] Kazi, Ankan. “Diminishing a Poet.” The Indian Express, June 14, 2017. Accessed May 16, 2019.

[v] Choudhury, Serajul Islam. “The Blazing Comet.” New Age Xtra. June 1, 2006. Accessed May 16, 2019.

[vi] Choudhury, Serajul Islam. “The Blazing Comet.” New Age Xtra. June 1, 2006. Accessed May 16, 2019.

[vii] Choudhury, Serajul Islam. “The Blazing Comet.” New Age Xtra. June 1, 2006. Accessed May 16, 2019.

[viii] Hasina, Sheikh. “113th Birth Anniversary of Poet Kazi Nazrul Islam and 90th Year of His Poem ‘Rebel’.” Address, India-Bangladesh Joint Celebration, Dhaka, May 25, 2012.

Image source: https://www.calcuttaweb.com/index.php?route=product/product&product_id=1127